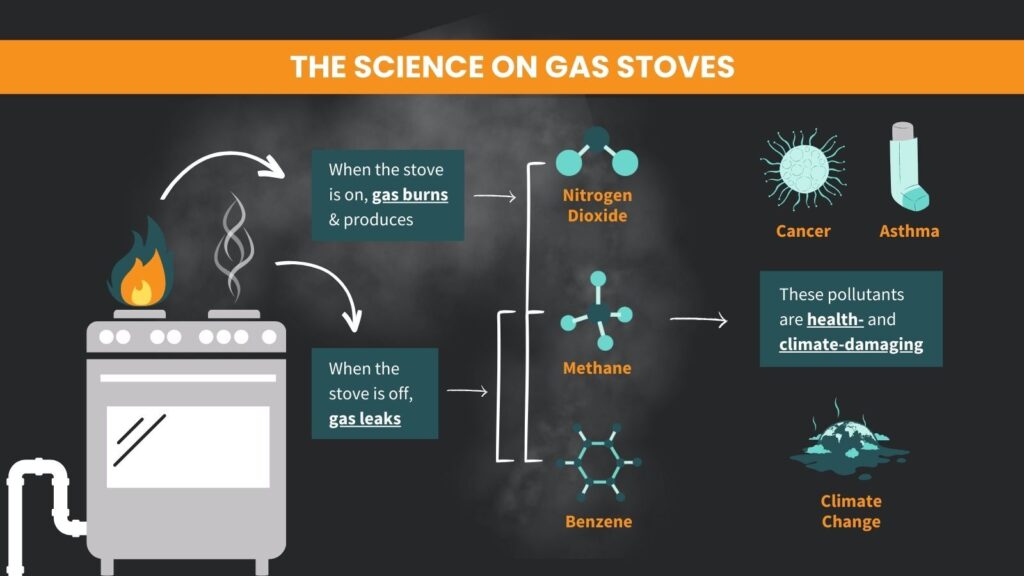

Few household appliances are as incendiary as the gas stove. After consuming national headlines for weeks in early 2023, many Americans are aware that research links gas-burning stoves to hazardous air pollutants and adverse health impacts, such as asthma.

Yet nearly 40 million households across the United States still rely on natural gas to cook. And while some state and city governments have moved to phase out gas-burning appliances, still others have moved to enshrine their place in America’s kitchens.

So what does the science show about gas stoves exactly? Let’s take a look back in time to see how scientific understanding of gas stoves has evolved.

1970-1980: Natural Gas and Indoor Air Quality

While gas industry insiders expressed concern about the byproducts of natural gas combustion as far back as 1906, it was the 1970s that saw the first flurry of scientific findings linking gas stoves to reduced indoor air quality. Of particular concern are nitric oxide, NO, and nitrogen dioxide, NO2, which together make up NOx. This class of gaseous, nitrogen-based pollutants are known respiratory irritants that occur when gas is burned at high temperatures, and they are now associated with the development of asthma.

In 1972, a preliminary study from the EPA found that NO2 increased to nearly 1.0 parts per million (ppm) in an unventilated kitchen cooking with a gas stove. For reference, that’s nearly 10 times higher than the EPA’s current 1-hour ambient air quality standard of 100 parts per billion (ppb). In 1974, a study by Yocom et. al found that unventilated gas cooking worsened indoor air quality by generating carbon monoxide (CO). Also in 1974, a publication by Wade et. al found that cooking with a gas stove increased CO and NOx, including nitric oxide (NO) and NO2, above outdoor levels. In 1980, a study by Dockery et. al investigated exposure to NO2 in households with and without a gas stove. They found that concentrations of NO2 were significantly higher in the home with a gas stove than in the home with the electric stove. In the same year, another study by Berk et. al found that indoor concentrations of pollutants, including NOx attributed to gas appliances, often exceeded outdoor standards.

1975-1980: Linking NOx and Respiratory Illness

At the same time that science was linking gas stove use to NOx production, studies were also beginning to find a direct relationship between these pollutants and respiratory illnesses. Between 1975 and 1980, at least six studies were published that investigated exposure to NOx and respiratory illness. In 1977, a scientific study noted a so-called “cooking effect,” whereby scientists observed that children from homes with gas cooking were more likely to have cough and bronchitis. They speculated that this might be due to the increase in NOx associated with gas cooking. Then, in 1979, research by Florey et. al found that children from homes with gas cooking had higher incidence of respiratory problems.

1981-1983: EPA Special Report and Congressional Hearings

In 1981, in light of studies demonstrating a link between gas cooking and potentially health damaging indoor air pollutants, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) commissioned a summary report from the Committee on Indoor Air Pollutants. This report mentions that “unvented gas cooking is probably responsible for a large portion of nitrogen dioxide exposures in our population” among other sources of pollution.

Following this report, government agencies like the EPA and the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) began investigating the need for indoor air quality standards. In 1983, the U.S. Congress held congressional hearings on indoor air pollution. Although these hearings did not lead to any indoor standards for natural gas, they nevertheless sparked serious civil debate about the place of gas stoves in the home.

1991-2015 – NOx, Gas Stoves, and Asthma

Between 1975 and 1991, at least a dozen studies were published that examined the relationship between NOx and respiratory illness, including asthma. In 1991, Hasselblad et. al performed a meta-analysis of the scientific evidence up to that point. A meta-analysis is a scientific review of the available literature on a topic at a given time. What they found was that a significant increase in exposure to NO2 increased the risk of childhood respiratory illness by 20 percent.

In the decades after the 1983 hearings and the 1991 meta-analysis, research continued to build a link between the use of gas stoves, NOx, and human respiratory illness. In 2013, researchers performed another meta-analysis. In this review, they specifically investigated studies tying gas stove use to respiratory illness in children. What they found was that children living in a home with gas cooking were 42 percent more likely to develop asthma.

Then, in 2014, a study from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory found that using a gas stove without a running vent hood resulted in 62 percent, 9 percent, and 53 percent of occupants being exposed to NO2, CO, and Formaldehyde levels, respectively, that exceed acute health-based standards and guidelines.

2010-2022: What’s in Natural Gas, Anyways?

Until this point, the vast majority of research on gas stoves focused on what is called “post-combustion” pollution. That is, the pollutants that result from lighting the stove and actively burning natural gas. In the past few years, science has begun to ask more questions about “pre-combustion” natural gas—providing new insights into the pollutants that gas stoves leak while they are turned off. We know that natural gas is 75-90 percent methane, which serves as the fuel source, but the chemicals making up the other 10-25 percent have, historically, not been well understood.

Studies find hazardous air pollutants in natural gas during extraction.

Between 2010 and 2018, several studies were published that found non-methane volatile organic compounds (VOCs) were present in natural gas when it is extracted. Volatile organic compounds are a class of organic compounds that can easily become a gas under normal indoor air conditions. Several of the compounds found in natural gas are of concern to human health, such as hexane, toluene, and benzene. Benzene is a known human carcinogen which has no safe level of exposure, according to the World Health Organization. In 2014, a study found that emissions of toxic hydrocarbons, including benzene, in the Denver-Julesburg in Colorado were significantly higher than the state’s inventory allowed. In 2016, researchers working in northern Texas found that there were significant benzene emissions downwind of oil and gas development.

Studies find hazardous air pollutants in natural gas during transportation.

In 2022, researchers at PSE reviewed publicly available gas industry data and found that transmission natural gas, or gas that is being transported from extraction to end users, contained on average 37 ppm benzene.

Studies find hazardous air pollutants in natural gas used in homes.

When someone turns on their stove, they are opening the end of a long gas pipeline that extends from extraction to use. Of course, natural gas goes through significant processing on its way from the ground to a stove, so it is logical to ask whether or not these pollutants actually reach the end user.

The first paper to quantitatively answer the question of what is in downstream (i.e., end user) natural gas was Drew Michanowicz’s 2022 Boston Study. Using metal canisters, the team collected unburned natural gas from residential stoves over two winters in the Boston area. What they found is that certain hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) are nearly ubiquitous in natural gas, including benzene and toluene, which were in 95 percent and 94 percent of the samples taken, respectively. Earlier that same year, a study published by PSE Healthy Energy Scientist Eric Lebel and Stanford University found that natural gas appliances—including stoves—leak methane, even while they are off. This is an important finding because it demonstrates a possible exposure pathway for any pollutants in unburned gas; if benzene is in unburned gas that leaks from a stove, then it is conceivable that people in the kitchen may be exposed to it. Additionally, methane is a powerful greenhouse gas, and residential leaks therefore contribute to climate change.

Then, in October of 2022, scientists from PSE Healthy Energy published another study looking at natural gas composition in California. Sampling gas from stoves throughout the state, they found that benzene was present in virtually all natural gas samples. Moreover, using the gas leakage rates from the previous Lebel et. al study, they ran indoor air models simulating potential benzene exposure and found that, given the correct circumstances, leaks from gas stoves can lead to elevated indoor benzene concentrations.

December 2022-June 2023: Asthma, NOx, and Benzene

In December of 2022, a paper published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health attributed roughly 12 percent of childhood asthma in the U.S. to gas stove use. Although surprising to many, the somewhat contentious findings of this study represent a continuation of decades of research. The publication of these results caused widespread debate, and brought the potential health ramifications of natural gas back to the forefront of the public consciousness.

In June of 2023, scientists at Stanford University and PSE Healthy Energy published a study investigating the pollutants that are created by using a gas stove. Using real time air pollutant analyzers, the researchers found that, in addition to NOx, burning natural gas can also produce benzene. Additionally, they found that the amount of benzene in the home while using a gas stove often exceeded health benchmarks. This finding adds a new dimension to the post-combustion (after the flame is lit) research that has been done so far, and highlights that benzene may be emitted from both sides of the flame.

Looking Ahead

Researchers at PSE Healthy Energy are continuing to investigate the link between natural gas and health-damaging air pollutants. This includes working to publish additional data that has already been collected in North America and collaborating with scientists at Stanford University to couple pre-and post-combustion findings. Additionally, PSE and Stanford have taken their research international; data has been collected in Australia and the United Kingdom, and researchers are working to conduct a sampling campaign in at least two European countries. This work will add to the already extensive research about the health and climate impacts of natural gas; both when it is being burned and when it leaks.

The science regarding natural gas and public health has a long history, and it is continuing to evolve. As we learn more, we are able to make better informed personal and policy decisions about our natural resource use. Look out for future studies and press releases from PSE to stay up to date on the most recent findings.