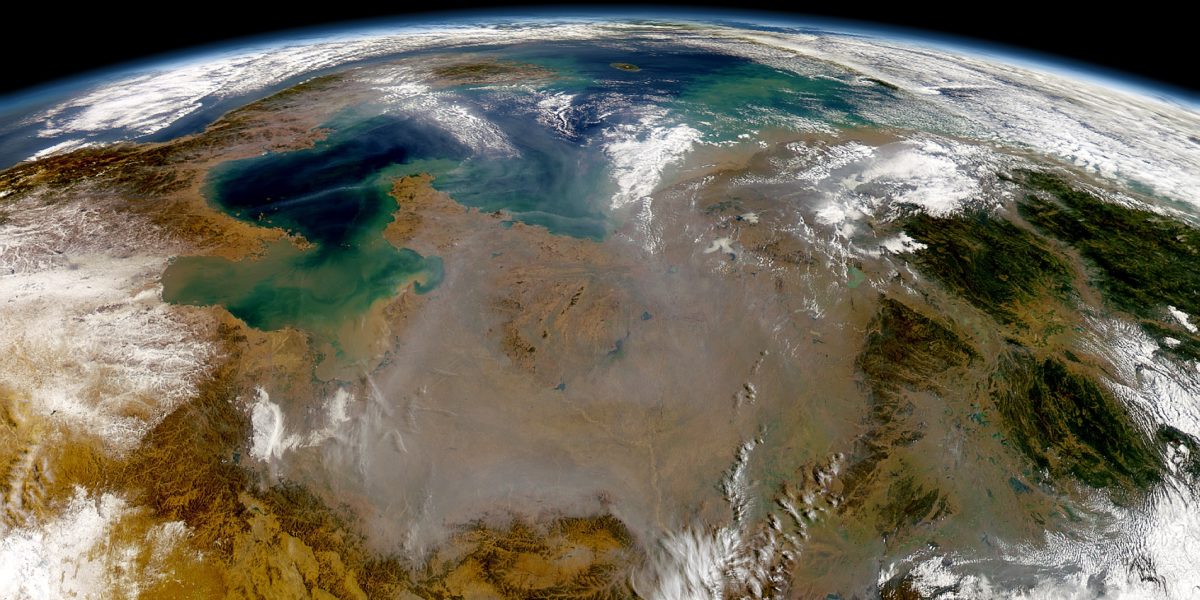

Above: Satellite image of Earth shows air pollution over China. Photo courtesy of NASA.

Global health benefits from climate change mitigation could amount to trillions of dollars annually, as eliminating sources of carbon emissions reduces health-damaging co-pollutants that contribute to premature mortality. Given these benefits, why aren’t countries acting more aggressively to curb fossil fuel combustion?

Standard cost-benefit models frequently omit health and other societal co-benefits of climate action, skewing the economic optimization of climate policy in favor of less ambitious, suboptimal mitigation pathways. Overlooking them not only reduces a complex interconnected global issue into an overly simplistic one, but also misses the opportunity to make a compelling economic argument for immediate political mobilization to combat climate change.

MISSING THE FULL PICTURE

Cost-benefit analysis is a methodology fundamental to policy and investment decision-making, used by governments, businesses, and other entities to evaluate potential investments. The framework is simple: calculate the costs of taking a particular action, quantify the economic benefits, and compare the results to determine whether the expenditure in question makes financial sense.

When it comes to climate policy, however, standard cost-benefit frameworks can be inadequate. Climate change is a global phenomenon with indirect consequences for many aspects of society and the environment. Cost-benefit models that consider the upfront costs of mitigation and adaptation measures without adequately valuing their societal benefits leave out a critical part of the equation.

Omitting the indirect costs of climate change – public health costs, wildfire damage, managed retreat – leads to pseudo-“cost-optimal” policies that ignore the cascading losses society will incur as the effects of climate change become increasingly severe. The co-benefits of climate change mitigation, including these avoided losses, are therefore undervalued.

RELEVANCE TO CLIMATE POLICY

Cost-benefit analysis informs climate policy and investment decision-making on a variety of scales. On a local scale, it might help an electric utility determine whether to invest in a new renewable energy project or instead repower an aging coal plant. Globally, a set of complex cost-benefit climate economy models like the Dynamic Integrated Climate-Economy model (DICE) are used to devise optimal policy pathways and to estimate the global social cost of carbon. DICE is a globally aggregated economic model developed by economist William Nordhaus and is one of the main integrated assessment models used by the U.S. EPA.

Given that cost-benefit models underpin influential climate decisions at every scale, incorporating estimates of co-benefits into existing frameworks is vital to ensuring that investments flow into the most impactful mitigation and adaptation measures.

VALUING CO-BENEFITS: A QUANTITATIVE CHALLENGE

Co-benefits of climate change mitigation are positive externalities, or societal “side effects,” that result from actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Examples include reduced health costs from improved air quality, increased thermal comfort and work productivity from energy efficiency retrofits, and job creation from investment in new sectors like renewable energy.

While often alluded to in discussions about climate policy, co-benefits are frequently excluded from quantitative cost-benefit analyses. One reason is that we lack the robust and standardized quantification methodologies needed to include them.

A primary challenge is to develop methods that capture location-specific effects of climate change while remaining applicable to different locations. Strategies for climate resilience need to be tailored to a locale at the regional or community scale, but the urgency of climate change requires that quantification methods and policy design be streamlined across many different geographies.

By nature of their being “indirect,” co-benefits can also be difficult to quantify. Consider a coastal city like Annapolis, Maryland, which is experiencing sea level rise at two to four times the average global rate. In deciding whether to raise its seawall, the city needs to weigh the cost of this project against the economic damage of potential flooding. Traditional flood damage valuations evaluate the physical damage to buildings and infrastructure, but this approach omits indirect economic losses like traffic disruption, missed work, and reduced visitation to flooded businesses. How can the city quantify the impact of traffic deadlock in its urban center? Or a decline in tourism due to frequent flooding? Whereas estimating the cost of reconstructing flooded buildings is fairly straightforward, evaluating the indirect impacts of flooding on other parts of the local economy is much more challenging.

While difficult to quantify, indirect impacts can amount to significant losses for flood-prone cities over time and are therefore critical to include in the valuation of climate-resilient investments. Predicting the behavior of a complex system involves uncertainties that make it difficult to develop meaningful projections. By developing a range of estimates with their corresponding likelihoods, however, researchers can facilitate the inclusion of co-benefits like climate resilience into cost-benefit analyses even if their exact values cannot be determined.

CO-BENEFITS ACCELERATE OPTIMAL DECARBONIZATION

Standard cost-benefit models conclude that the globally optimal policy for carbon emission reductions incurs net costs for most of the 21st century. When researchers quantify and include the health co-benefits achieved through the reduction of local co-pollutant emissions from fossil fuel combustion, however, global net savings begin immediately and full decarbonization occurs sooner, compared to a base case that focuses only on climate effects.

Importantly, optimal decarbonization is more aggressive than the base case even when testing alternative values for variables like the assumed level of air quality control occurring independently of climate policy, the discount rate used to weight present against future well-being, and the monetary value of a human life-year. These results demonstrate that it is still possible to draw informative conclusions for climate policy even when the value of co-benefits are subject to numerous uncertainties.

Are global cost-benefit models politically actionable, however, even if they suggest trillions in net savings? Who will see these savings, and who will bear the costs? In reality, money cannot simply be transferred between different sectors or countries to align perfectly with what is optimal. Leveraging the value of co-benefits will therefore require governments to break down silos between sectors like health and energy where possible in order to maximally optimize across them.

THE ETHICS OF MONETIZATION

Incorporating health co-benefits into climate policy models brings to light another challenge: the ethical dilemma of placing monetary values on non-monetary benefits. How can we place a dollar value on public health or resiliency? Do we corrupt certain elements of society by treating them as market commodities with a price tag?

Monetization incorporates bias by assigning values to benefits that don’t have an explicit market price. Discount rates likewise introduce bias by weighting the well-being of present society against that of future society. Should we value present and future generations equally (a discount rate of zero), or should we value the well-being of people alive today over the well-being of humans who’ve yet to be born?

These philosophical questions complicate the monetization of co-benefits and suggest that some aspects of society might be better governed by political mandates (prohibiting power plants to be located within a certain distance of local communities, for example) rather than cost-benefit models. Despite the moral limitations of monetization, however, it is imperative that we incorporate estimates of co-benefits into policy frameworks that currently omit them altogether. In addition to justifying more aggressive climate policies, bringing co-benefits into the spotlight might help to highlight the ways in which traditional monetary valuations fail to capture important societal externalities.

TRAGEDY OF THE COMMONS

Historically, co-benefits have been thought of as peripheral to our primary climate goal of reducing carbon emissions. When we focus solely on carbon emission reductions, however, fighting climate change is plagued by the “free-rider” problem. Because individual countries benefit from carbon mitigation that takes place elsewhere, it is in their interest to wait for other countries to incur the costs of carbon abatement rather than act aggressively to reduce their own emissions. Unlike climate effects, however, the health impacts associated with the reduction of co-pollutants from fossil fuel combustion are localized. Health costs from air pollution in the top 15 GHG-emitting countries amount to over 4 percent of their GDP. Quantifying health benefits and other domestic co-benefits can make the case for aggressive climate action by individual countries, regardless of the level of action taken by their counterparts.

As policy-makers are often concerned with short-term costs and tangible benefits to their constituents, making costly investments in climate resilience and carbon abatement can be difficult to justify. The benefits of climate change mitigation accrue over an intergenerational timescale, but the costs largely fall on society today. The resulting philosophical and political dilemma can be difficult to resolve. Because co-benefits like improved air quality occur locally and affect people in the short-term, they offer a potential solution to intergenerational equity concerns as well as the international collective action problem posed by climate change.

MOVING FORWARD

If we can estimate the value of co-benefits, standardize the methodology of doing so, and facilitate their inclusion in local, national, and international decision-making, it might be possible to spur the level of political action required to keep global temperature rise under 1.5° C.

From an ethical standpoint, it can be difficult to place monetary values on co-benefits like public health that should be treated as moral imperatives. But as long as mitigation efforts continue to be stymied by the question, “How will we pay for it?” it is critical to estimate the co-benefits of ambitious climate action, prompting decision-makers to ask instead, “How much will we save?”

Perhaps highlighting the value of co-benefits will prompt a new discussion altogether – one that investigates the limitations of traditional cost-benefit analysis and challenges its role in governing our societal approach to equity, health, and the environment.