Meet Sofia Bisogno, BSE, Air Quality Scientist at PSE Healthy Energy. Sofia’s work clarifies how methane-linked hazardous air pollutants can put public health at risk.

Sofia in the field as part of her undergraduate research. Photo by Sneha Iyer.

What’s your scientific background?

I got my Bachelor’s of Science in Engineering from Princeton. I knew I wanted to do climate work, so I studied under professors who were doing air quality research. Atmospheric chemistry skills are transferable to climate because in both cases you’re looking at pollution sources. After graduating, I worked in air quality consulting for three years. Then I came to PSE.

What was consulting like?

I graduated May 2020 and got a job as an air quality and sustainability consultant, mainly helping different industries in the Bay Area meet the requirements of the California Environmental Quality Act. We assessed the pollutants that a new project would emit, and what the project’s potential health impacts would be in the surrounding area. If the projected emissions exceeded legal thresholds, we found ways to reduce them. I worked mostly in the commercial real estate sector, but I also did some heavy industry and some energy industry work.

Did you like the job?

It was a great first job. I felt like I was in the inner workings of how policy plays out in the real world, which was super interesting. I saw firsthand how no company, no industry, would do anything beyond what a regulation required. Whatever the threshold was, the task was to make sure the company was going to be juuuust under it. It solidified my understanding that progress made on air quality and climate is only as strong as the regulation requiring it. That experience proved to me that improving air quality is not a technical problem. It’s a policy problem.

So how did you find your way to PSE?

In that job I was also doing a lot of public health calculations, and I really liked that work. When I found a way to get the cancer risks from a given project down below a certain threshold, that felt like real impact. But I was confused at how I could combine my interest in air quality, public health, and climate. Then in the summer of 2023, I saw that PSE was hiring an air quality modeler to work in decarbonization. I thought, “Wow, they made a job specifically for me!”

So what do you do here at PSE?

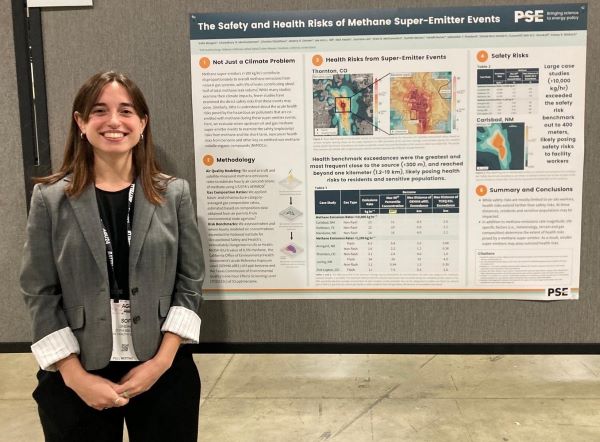

Right now, I’m working on a web tool called the “Methane Risk Map” that will map the health risks from methane super emitters. In preparation for launch this summer, I’m analysing a lot of data, running air quality models, figuring out how to make meaning from different data sets.

Sofia presents her research on the public health risks of methane-linked hazardous air pollutants at the American Geophysical Union’s annual conference in 2024. Photo by Nick Heath.

Can you talk about what goes into that?

It’s a massive project. There’s a team analyzing gas composition, a team that models air quality, a team that examines the burden that air pollution puts on communities, and there’s a team that’s focused on building the webtool itself. Every team is making these complicated decisions and advancements. And then we all meet and share our progress. We’re moving the ball forward independently, and also building something together.

What was your most memorable day at PSE?

In the early stages of developing the Methane Risk Map, we held listening sessions to hear from different organizations about their needs and how they might use the tool. The first time we presented an early draft of the Methane Risk Map to a community organization left a big impression on me.

The organization is in a community that is already overburdened from other sources of pollution–trucking, e-commerce, warehouses and stuff like that. A lot of people in the community already have asthma. And in the Methane Risk Map, they’re seeing yet another source of pollution that puts them at risk. For me, sitting at my desk, it’s data, it’s modeling. But for everyone else, it’s the air they breathe, it’s their kids’ health. That’s scary.

It was my first time witnessing the emotional impact of our work on someone who’s seeing our work for the first time. It made the work very real to me.

What do you do when someone’s response to your work is fear, anger, grief, or frustration?

I try to listen and experience those feelings with them. It is tempting to avoid the painful feelings, to default back into the science. But it’s important to empathize with someone who’s learned something scary. I try to breathe through it, and I also let it inform my work. That conversation got me thinking: how can we talk about risks without overwhelming people?

What do you say to someone with a more resigned reaction? Someone who might say something like, “Oh well, one more thing that’s going to give me cancer.”

That’s totally valid, and it’s a reaction that I have myself sometimes. I don’t expect people to consult the Methane Risk Map to make personal decisions about their lives. This is not something that can be solved by each person upending their lives to avoid air pollution. This is a policy issue. This is a bigger picture issue.

What is something about PSE that you think would be hard to find somewhere else?

I think that doing research in such an applied way is rare. We find partners in the real world to collaborate with and we figure out how to support the work that they do, whether that is in communities, or in legal proceedings, or something else. Plus we are a small team doing big things, so there are a lot of opportunities for growth and learning. That’s unique.

Can you tell me about a time when you saw your research applied in “the real world”?

The New Mexico Environmental Law Center was pushing for a new health-protective regulation in Bernalillo County, to require that new projects go through a more rigorous air permitting process that included public health impacts and environmental justice considerations. PSE’s role was to provide a scientific analysis of how stricter air pollution regulations would benefit the surrounding communities.

It was similar to the regulatory work that I had done in California, but instead of serving a client trying to comply with the regulation, I was serving a partner trying to draft the regulation. It was the kind of work I wanted to do my whole life – to advise policymakers on what they need to take into account when they draft health-protective policies.

Was the policy implemented?

I should clarify that PSE doesn’t lobby or advocate for policy. We do the modeling to show: if you do X, then Y is the impact on public health. It’s up to the policymakers and governing bodies to determine what is most important to them, and how to balance the interests of their various constituencies. The county went through a process to determine the regulation that suited their priorities. Ultimately, a version of the policy was implemented.

It was inspiring to see how environmental lawyers fight for stronger public health protections. Watching everything unfold was also a crash course in how power works. It was clear that whoever had the most resources had the most opportunity to exert pressure and dominate the political process. I think about the communities who are systematically underresourced. How do they advocate for themselves in this very specific, complicated and unbalanced system? To say it’s an uphill battle is an understatement.

Do you feel optimistic about the potential for progress on air pollution?

There are a lot of really great people working in policy and community advocacy. I know people in government who really care and are pushing things forward. I’ve met those people. They exist. I have faith that if we’re all working on it, something good will happen.

Sofia and her cast in rehearsal for her senior choreographic thesis, “-rrosa,” inspired by tango and other music from her parents’ home country of Uruguay. Photo by Jon Sweeney and the Lewis Center for the Art.

What do you do when you’re not working?

I dance. I trained my whole life in ballet and contemporary dance and even minored in dance in college. These days I’m branching out and taking tango lessons. My family is from Uruguay, so I grew up listening to tango music at home. My goal is to be able to dance at tango socials when I visit my family in December. I’m not there yet.

What would you say to a young person who’s considering a career in research?

If you’re interested in research for impact, you need to delve outside of your concentration and take classes in other fields–sociology, anthropology, history, literature. Expand your technical formation to include arts and social sciences. It will help you be a better communicator, a better citizen, and a more impactful scientist.