Meet Dr. Yannai Kashtan, PhD, an Air Quality Scientist at PSE Healthy Energy. His research has provided insight into the health risks associated with indoor air pollution from gas stoves.

Q: Tell me a bit about your scientific background.

A: I was homeschooled all the way through high school, which let me really explore my scientific passions. I fell in love with chemistry and then physics, so when I went to Pomona for college I majored in both. I went to graduate school at Stanford, where I got my Master’s in chemistry and my PhD in Earth System Science. I studied the air quality of the micro-environment of the home, and in particular the impact that gas stoves have on indoor air quality.

Q: Did homeschooling allow you to really focus on science?

A: It allowed me to focus on a lot of things. My obsessions rotated. But yes, science–chemistry in particular–was one that persisted for a while.

Q: I’ve heard rumors that you had a chemistry lab in your garage.

A: I did, and I had a YouTube channel where I posted my experiments.

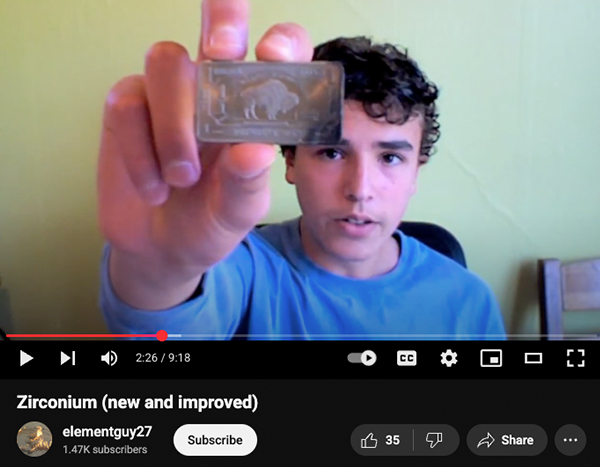

Young Yannai displays a bar of zirconium before he torches it to test its heat resistant properties in his garage chemistry lab in 2014. Photo courtesy of Yannai Kashtan.

Q: Why the YouTube channel?

A: I like the challenge of figuring out how to take something complicated and distill it down so that anyone could understand without dumbing it down. And as a kid and a teen, it was also a way to connect with people and nerd out about whatever I was obsessed with at the moment. I guess I always thought that sharing what I learned was just part of what science was about. I didn’t know it was a separate skill until I got to college.

Q: Did you ever have any mishaps in the garage chemistry lab?

A: I got really into rocketry for a brief period, which was a bad idea. A rocket propelled by sugar and saltpeter landed in the neighbor’s yard. To be fair, I didn’t have any genuine mishaps that involved actual injury, beyond some singed hair.

Q: What singed your hair?

A: It was rocket fuel.

Q: Ok, so some singed hair, but nothing more dangerous with all these chemicals you’re working with?

A: The most dangerous chemical I ever had in the garage was 50 milliliters of liquid benzene, just pure 100% liquid benzene. I bought it because I was really excited about it, and then as I read more about it I got too scared to open the bottle, so I never used it and I just brought it straight to the hazmat disposal facility. It was the only chemical I had that I never opened.

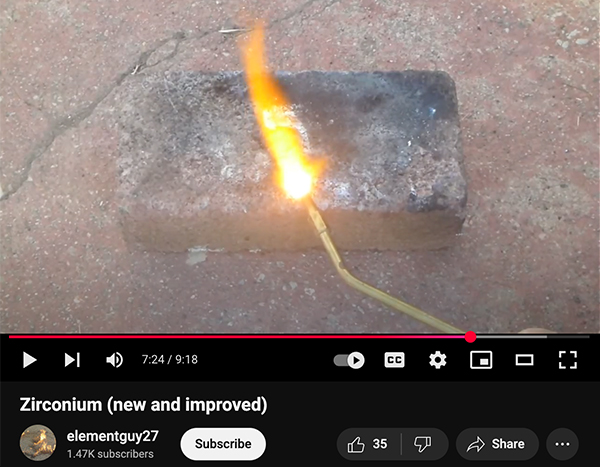

Yannai uses a welding torch to try to set a bar of zirconium on fire. Instead, he creates zirconium dioxide. Photo courtesy of Yannai Kashtan.

Q: I’m sorry? What were you planning to do with the benzene?

A: It’s hard to imagine what I was thinking when I ordered it, but all I can say is that I was a collector. I had a coin collection. I had an element collection. I just thought it would be cool to have it. It arrived in this big canister with a bunch of highly absorbent, fancy, scientific kitty litter in case it spilled. It had a bunch of warning stickers on it. There was only one company that would even ship benzene to a residential address. I understand why now.

Q: So you got a container of benzene delivered to your doorstep as a kid, and then you got your PhD studying benzene produced by gas-burning household appliances. Did you feel like you had come full circle in some way?

A: It is a funny coincidence. All I can say is that the more I learn about benzene, the happier I am that I never opened that bottle.

Q: What was it about air quality that caught your attention?

A: When I was a freshman in 2016 my general interest was in environmental science. I thought I wanted to be a technologist, to develop something that can compete on the market. But by the time I was in grad school I began to realize that we have almost all the technology we need to solve climate change, cut air pollution, and live our lives with a much lower environmental impact. The bigger challenge was to implement the solutions we already have. That requires a lot of things, including informing people of the various downsides of fossil fuels –– including climate change and direct health impact –– and of the many solutions we already have.

Yannai collecting indoor air pollution data in an NYC apartment with a gas stove in 2022. Photo courtesy of Yannai Kashtan.

My advisor, Dr. Rob Jackson, asked me if I wanted to “work on stoves.” I was skeptical about spending my PhD researching a household appliance. But I thought, “Well, we’re looking for benzene, and I’m a chemist, so let me give this a chance.” And I did and I was totally surprised by what we found. It was way more interesting than I anticipated, and other people were way more interested in our work than I could have ever dreamed. So, really, I got into air quality by luck just by studying pollution from gas stoves–and it totally snowballed beyond what I ever would have imagined.

Q: And you found it satisfying?

A: As I learned more about it and realized what a big public health issue indoor gas pollution is, and how much people’s lives could be improved, and how many people this research could touch, I became interested in it just by working on it. So the interest followed the action.

It was different from what I had been doing before, which was using a multi-million dollar transmission electron microscope to look at nano crystals and stuff like that. But studying indoor air pollution from gas stoves was clearly having a bigger real-world impact than anything I had done prior. And it was a multi-dimensional challenge because it wasn’t just about the science. There was communication and politics; there were policy implications. It tickled different parts of my brain than just being in the lab.

If you rewind five years, I was seduced by the flash bang technology stuff. Then I became interested in the more quotidian. What if we make the air that everyone breathes like 10% cleaner. That’s actually way more effective at protecting people’s health and the environment than all the fancy stuff.

Q: So what do you do here at PSE?

A: I do a lot of field work. I help with measuring air quality in different settings and I help write up our findings and publish them in journals. I have a role in communicating our research, so I speak to journalists, policymakers, and other researchers. I also spend some time helping to think of new research projects, and get them off the ground by answering early stage questions, like how do we actually go about measuring a new kind of thing that hasn’t been done before?

Q: How do you see your work making an impact?

A: I see a big impact in the blend of rigorous science and effective communication. There had been plenty of studies on gas stove pollution, for instance on NO2 emissions, going back decades. But I think that, along with research from RMI and others recently, our studies’ breadth and rigor and effective communication really helped launch the issue of gas stove pollution into the public consciousness.

Anecdotally, I know lots of people who read the research–not through me–and who now are considering electrifying. So I think it has made a big impact on the public’s awareness and associated action.

I recently got to present the research at a hearing at the California Energy Commission, and hearing from them about how our work is going to be incorporated in their own thinking and internal processes was very cool. I always was interested in impact, and it’s gratifying to see evidence of it.

Q: What does it feel like when people deny the findings of your work?

A: It’s a mix. There is frustration of course, but also a lot of curiosity about what’s motivating their denial. Where is it coming from? Where is the breakdown in trust coming from? How can I help rebuild trust? I trust the scientific process. It has feedback loops and internal correction mechanisms so that no one scientist has to be perfect. Scientists are humans and humans make mistakes. But science is a collective enterprise. And my belief is that it’s one of the best ways we humans have figured out to learn about our world and actually increase our collective knowledge about our world over time.

Yannai takes a break after completing a 50-mile run in 2020. Photo courtesy of Yannai Kashtan.

Q: Tell me about your hobbies.

A: I go camping and hiking and long distance running. My longest was a 50 miler that I did just after graduating college. It was in the Rocky Mountains. So there were big climbs and much of the course was over 10,000 feet. It was hard. I tried again a few weeks ago, but my IT band crapped out at mile 32 and I dropped out. But hopefully one day I’ll do 50 miles again.

Q: Do you have pets?

A: Yes, I have two cats. They enrich my life and impoverish my sleep. Their legal given names are Neuron and Bismuth.

Q: What would you tell young people considering a career in scientific research?

A: Science is so many things. It isn’t one thing and it doesn’t have to look like what your idea is of science to be science. Often some of the most interesting science probably looks not at all like science (and conversely, some things with the patina of science are not). If you want to ask systematic questions about the world and to get answers, then maybe you want a career in science.