New Research Can Help Integrate Affordability, Public Health, and Climate Into Energy Planning

Electricity bills in the U.S. jumped five percent on average last year—the largest annual increase on record. Such increases can be particularly hard on low-income households who may face impossible choices between paying utility bills and paying for other essentials such as rent, food, or medicine.

To ease the burden on consumers, state and federal policymakers have pumped billions into bill assistance and energy-saving programs. Technologies, such as electric heat pumps and home insulation, can reduce household energy bills while simultaneously improving health and reducing carbon emissions. The question is: how can we ensure that these technologies reach those who need them most?

Over the past two years, PSE Healthy Energy (PSE) has researched strategies to increase energy affordability for low income households. Looking at census-tract level data throughout Colorado and Maryland, we’ve examined who is paying more on energy costs (as a percentage of income) and why. While every household has a unique story, we’ve found that investments in energy affordability can go farther and reap greater benefits when they are integrated into utility planning.

Integrating Affordability Into Utility Planning

Many utilities in the U.S. are required to develop Integrated Resource Plans (IRPs) that outline how the utility will reliably meet their customers’ projected energy demands. These plans are one powerful, but largely overlooked, opportunity to integrate affordability in energy planning. In a previous blog, we laid out some of the metrics that can help utilities take stock of the health and equity impacts of their investments. Now, we take a look at energy affordability.

Utilities across the United States use IPRs to weigh the pros and cons of a wide range of energy investments and technologies. Depending on the state, IRPs may compare large-scale supply-side investments in utility infrastructure, such as gas peaker plants or solar farms, against investments in distributed energy resources, such as energy efficiency, demand response, or residential solar.

Generally missing from this analysis, however, is the impact that household-level investments have on energy affordability. This is partly because those impacts are hard to measure at the household level. That is, until now.

Models recently developed by PSE allow us to more accurately estimate how much income individual households spend on energy and to calculate the potential benefits of specific clean-energy interventions. These insights can be incorporated into IRPs to help utilities, policymakers, and communities determine which investments will yield the greatest total benefit for society over the long-term. By asking public utility commissions across the country to set their sights on minimizing energy cost burdens, we can move one step closer to creating an energy system that is both clean and more just.

Key Concepts in Energy Affordability

Faced with higher energy costs, consumers have three choices: use less energy, invest in energy-saving measures, or manage their own energy with technologies such as rooftop solar or storage. Yet many low-income households can’t afford to do any of these. Low-income households tend to use less energy than wealthier households, yet pay a far greater portion of their income on energy costs for their homes.

To understand how we can align government and utility investments with energy affordability we’ll use two key terms:

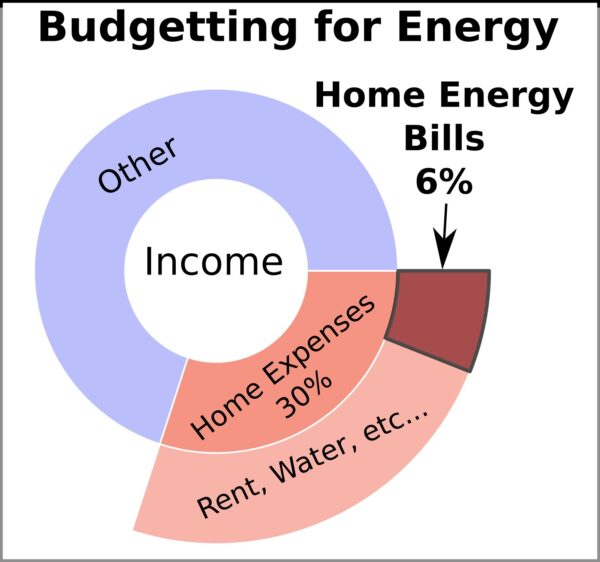

Energy-cost burden: This is the percentage of household income spent on home energy needs. Households with energy cost burdens greater than six percent are typically considered overburdened (Figure 1). As a metric, energy cost burden helps to compare average energy affordability across different populations and different geographic areas. It also helps to identify those households that are most likely to benefit from assistance with their energy bills.

Figure 1

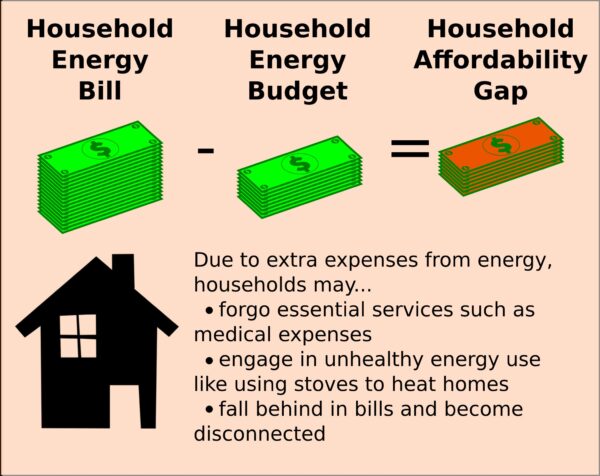

Energy affordability gap: This is the amount spent on energy bills in excess of six percent of income (Figure 2). Each household has an estimated energy affordability gap. These household gaps can be added together to calculate cumulative gaps within states or utility service territories. As such, this metric helps us quantify the full scale of the energy equity problem by representing the total societal cost of achieving energy affordability across the board—say, by providing bill assistance to bring everyone’s energy expenses to below six percent of income.

Figure 2

Modeling the Value of Saved Energy

Many bill-assistance programs exist to help households pay their energy bills and meet their basic human needs. While vital, such programs need continual funding and fall well short of the total funds needed to eliminate the affordability gap of all households. In Maryland, we estimate that the total energy affordability gap is roughly $400 million annually. That means that $400 million is needed each year to help pay down energy bills so that all Maryland households have energy cost burdens below six percent of income. Yet only $120 million is currently available in bill-assistance. Furthermore, bill assistance does not help meet climate targets, nor does it make our homes healthier and more efficient.

The more sustainable and long-term solution is to improve homes with specific clean-energy interventions that lower the energy affordability gap year after year. As households save energy, they save money and lower demand for bill assistance. In time, only the lowest-income households would continue to receive some form of bill assistance.

So how do we go about quantifying the costs and benefits of lowering the energy affordability gap with home interventions?

Historically, the complexity of generating reliable estimates of the energy affordability gap has limited its use for decision-making. For privacy reasons, energy bills are not publicly available and so researchers have had to use estimates. This is challenging since energy bills are driven by a host of diverse factors—including climate, family size, house condition, home age, heating fuel type, local energy prices, structural inequities, etc.—and because income strongly correlates with energy bills. Often, researchers use a “typical” household in a given area to estimate that area’s energy cost burden. But this approximation cannot reliably produce accurate estimates of the cumulative energy gap because energy burdens can vary substantially around a representative household within the same neighborhood.

To solve this technical problem, we use modeling to simulate each household’s energy bill and income. Using this modeled dataset, we can generate the most accurate and fine-grained estimates of household energy affordability gaps to date and estimate how investments in energy affect energy needs, carbon emissions, and the financial burden on low-income households. We then break down energy bills into the energy needed to heat the home, cool the home, heat water, and run all other appliances such as stoves and refrigerators .

Breaking down household energy use allows us to pinpoint the causes for high energy bills, and the cures.

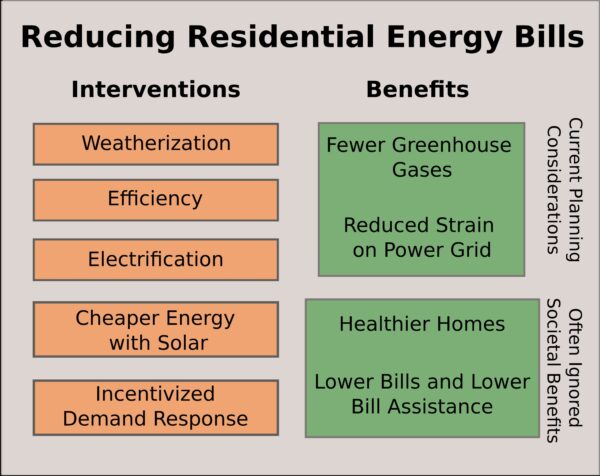

Many interventions can help reduce a household’s energy bill (Figure 3). For example, a home can be weatherized by installing insulation, or made more efficient by replacing old and inefficient appliances. Rooftop solar or subscriptions to community solar programs can further lower energy bills. By investigating how much these interventions cost and how they affect energy bills, we can propose ideal pathways for eliminating affordability gaps and prioritize those households that stand to gain the most from such improvements. Importantly, these low-income programs can provide overall savings in a matter of just a few years by reducing the amount of funds that would have otherwise been needed in the form of bill assistance.

Figure 3

Making Integrated Resource Plans (Even More) Integrated

Programs that provide home interventions to improve energy affordability for low-income households are often run by utilities, states, or the federal government. Utilities across the country are required to develop Integrated Resource Plans, reviewed by public utility commissions on a bi- or tri-annual basis, to determine the optimal mix of energy resources that need to be added to the grid to meet projected demand at a minimum cost, while also meeting climate targets. Unfortunately, efficiency, electrification, and solar programs for low-income households are often evaluated separately. Despite the fact that such programs help meet climate and energy goals, they are most valuable when their difficult to quantify societal benefits are included. Armed with the ability to predict the evolution of the energy affordability gap under such programs, we can now ask public utility commissions to minimize this gap over time by requiring utility companies to incorporate low-income efficiency, solar, and electrification programs into their Integrated Resource Plans.

Because resources such as low-income efficiency or community solar are often more expensive to the utility compared to non-low-income efficiency or utility-scale solar, one could argue that including such resources in IRP modeling would lead to a tradeoff between reducing energy cost burdens on the one hand and achieving lower greenhouse gas emissions and lower resource costs on the other hand. The total cost of the energy resource mix that IRPs currently optimize for, however, does not represent the full societal cost of these resources and omits key market externalities, such as their health impacts and the size of the energy affordability gap.

These societal costs are real and are borne by ratepayers, whether by increased healthcare costs from air pollution, or by funding bill-assistance programs needed to cover the annual energy affordability gap. IRPs currently serve the purpose of optimizing for the lowest-cost portfolio of electricity generation resources that meets both climate targets and projected demand over the coming decades. When we expand our scope beyond just utility costs to include the cost for bill assistance represented by the affordability gap and additional societal costs associated with public health and inefficient homes, low-income programs often pay for themselves in a matter of a decade or less. To support states’ energy equity and environmental justice goals, it is therefore reasonable to expect that IRPs also incorporate air quality and energy affordability targets with the goal of guaranteeing resource adequacy at minimized societal costs inclusive of the energy affordability gap and of health impacts.

Choosing to Plan for a More Just Energy System

Ultimately, planning for energy affordability is an ethical decision, with broad implications for environmental and social justice. In recent years, researchers have worked to develop a conceptual framework for energy justice. This framework delineates an energy system that distributes the benefits and costs of energy services and resources fairly, corrects for historic and structural inequities, and contributes to an impartial and fully representative decision-making process. By incorporating affordability metrics such as the energy affordability gap into the IRP process, public utility commissions across the country can help level the playing field for investments in low-income efficiency, low-income electrification, community solar, and demand response. This will ultimately save ratepayers billions of dollars while simultaneously supporting a healthier, greener, and more just energy system.